Our Fragile Community

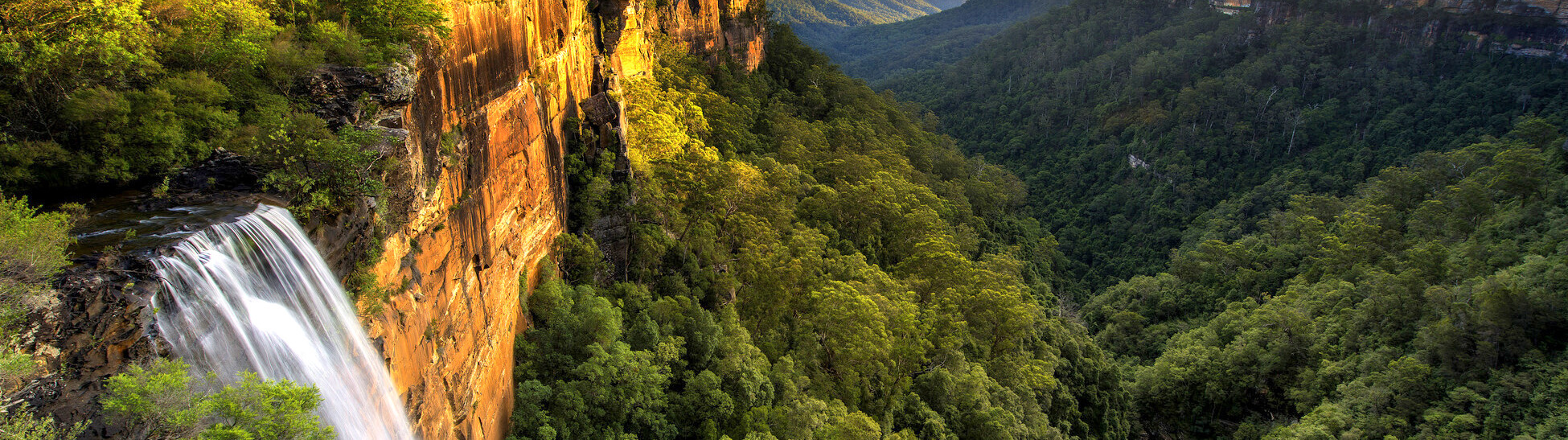

Vast areas of the Southern Highlands evoke a sense of pristine wilderness. And in some ways, it is. Look closely at the sheer-walled escarpments fractured by foreboding waterfalls. The lush rainforests and hidden grottoes. The serpentine waterways that intersect impossibly rugged bushland — woodlands strewn with towering eucalyptus, banksia and acacia. Natural havens where the silence and solitude are only broken by an overture of bird calls and rumbling skies.

Yet few know of these hidden worlds and the wildlife habitats that are fast disappearing to incursions caused by our insatiable appetite for forested resources and urban space.

At Native Wildlife Rescue, we believe that the Southern Highlands community has a pivotal role in preserving its natural heritage. This includes addressing the regulatory actions and environmental threats impacting fragile wildlife habitats within and beyond our national parks and state forests.

According to the [former] NSW Environment and Heritage Office, the Southern Highlands Shale Forest and Woodland supported 24 state and nationally-listed threatened species in 2017 — amphibians, reptiles and birds [including the ‘gang gang’ and glossy cockatoo, turquoise parrot, hooded and scarlet robin and the once robust owl]. Also joining them in the wake of the 2019-2020 Black Summer mega-fires were grey-headed flying foxes, yellow-bellied gliders and our iconic koalas.

But much of our native wildlife is already at the crossroad.

For the past thirty years, populations of spotted-tail quolls have been vanishing at a breakneck speed. Now classified as an endangered species [under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999], quoll sightings in the Southern Highlands’ woodlands are even rarer.

In February 2022, the NSW Koala population was also certified as Endangered under the EPBC Act.

Peer into the immediate future, and you will see identical scenarios with other species. Among them is the critically-endangered regent honeyeater, which feeds on the nectar from eucalyptus trees and acts as a pollinator for much of our native flora.

Today, conservation sources estimate that between 800-2000 regent honeyeaters only remain in Australia, with most living in the box-ironbark woodlands along the Great Divided Range.

Sadly, the ecological carnage remains inescapable for much of the region.

Since European settlement in the 1830s, the Southern Highlands has lost almost 90 per cent of prime bushlands — particularly the broad terrain surrounding Morton National Park, cleared for forestry, agriculture and urban development in the 1960s.

No matter which direction you travel in the region, you will see complete ecosystems fragmented by roads, fences, power lines, roadside rubbish and an endless expanse of subdivisions and industrial centres.

Even the eucalyptus forests that survived the Black Summer [Green Wattle Creek, Currowan and Morton] mega-fires are now rife with unmanaged fuel loads — a composite of tinderboxes ready to ignite in the next cyclic drought.

Of the many environmental groups and agencies seeking immediate change to the pending wildlife crisis, the federal and state governments are not among them.

The Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment [formerly the Department of Environment and Energy] recently declared that the Southern Highlands Shale Forest and Woodland’s ecological community would not require a recovery and threat abatement plan.

Nevertheless, land degradation shows no signs of slowing down, with many enterprises and some private landowners pillaging the vast tracts of native bushland that were once prime wildlife habitats.

Time, however, is running out.

Our wildlife is teetering on the edge of oblivion. And the trickling of conservation efforts, including uprooting wildlife to far-flung sanctuaries, will not save our region’s imperilled species.

When they are gone, they are gone forever.

Endangered Koalas

Over 2 million Koala habitats were scorched during the 2019 | 2020 Black Summer mega-fires.

Despite the widespread destruction, Forestry Corporation of NSW has intensified its harvesting operations in unburnt old-growth forests. It’s time to determine what we value most.

In a race for survival, World Wildlife Fund [WWF] announced that our iconic koalas in NSW would likely face localised extinction by 2050. With over 200,000 hectares of forest harvested annually across the nation, it’s not hard to foresee where this will end — and all too soon.

Already, prime habitats are compromised by a rapidly-changing ecology and human activity. But in the aftermath of the Black Summer mega-fires and the recent NSW floods, any possibility of significant and now officially-endangered koala populations surviving in NSW’s unburned forests looks even more insidious.

According to the NSW Environment Protection Authority [EPA], over 5 million hectares, including 890,000 hectares of native state forests, were scorched. They included 85 per cent of old-growth forests on the South Coast and 44 per cent on the North Coast.

Although some koalas pulled through the carnage — many with scolding burns to their bodies — over 6000 species and hundreds of thousands of other endemic wildlife perished across the state.

There is no question that charred forests can rebound in regions where favourable climate conditions trigger the cyclic process of regeneration. However, adequate time is still required for ecologists to ascertain the full impact on broken ecosystems and monitor threatened species as they renew or adapt to the changing environment.

Yet contrary actions by the state-owned Forestry Corporation of NSW saw logging operations intensify at pre-fire levels in surviving old-growth forests before the last ember was extinguished. The fragile koala habitats logged included the Lower Bucca State Forest, which forms part of the designated Great Koala National Park — a primary component of the $45 million Koala Strategy. The policy, however, prioritises the protection of the iconic marsupials and their habitats and remains a classic example of conflicting Federal and State legislation at the heart of environmental issues.

Beyond the climate crisis we are now facing, our natural heritage has been further compromised by Regional Forestry Agreements [RFA Act 2002], a self-regulatory framework that allows the Forestry Corporation of NSW to bypass Commonwealth approvals under the Environment and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Please view the link to note the multiple amendments.

Currently, three RFAs in the state cover 2 million hectares of forest in Eden, North East and the Southern regions. The regional framework and rules, which fall under Integrated Forestry Approvals [IFOAs], are expanding further on the agreements. This includes how all state-run forestry operations must satisfy Commonwealth environmental requirements and the review process.

There are also four IFOAs in effect, which are carved into another composite set of self-regulated policies and practices. The fourth region; Coastal IFOA, covers the old-growth forests east of the Great Dividing Mountains in NSW, which is further absorbed into regional tenements; the Southern Highlands along with Eurobodalla and the western region of Monaro.

Approximately 13 per cent of NSW’s koala population lives in the Southern Highlands’ region. And the dire connection between rapid deforestation and their dwindling numbers is profound.

Though logging is vital to our economy and human consumption, the repealed provisions and legislation loopholes have weakened the environmental laws and the effectiveness of the NSW Environmental Protection Agency. For this reason, we must have a sense of an even larger purpose — to engage in parliamentary actions as a community. This includes calling for completely reforming our forestry industry and conflicting conservation legislation acts.

Please view our VIC Forest blog.